The ‘Domestic Workers Bill of Rights’ could change working conditions for 30,000 people in Seattle

When Rocio Burgos, 34, started working as a housecleaner for a family in Seattle, she didn’t also sign up to be a nanny. The parents who hired her expected her to look after their child, anyway.

That didn’t seem fair to Burgos, who made about $5 an hour working 11-hour shifts. “But when you need a job, you just can’t say no,” she said.

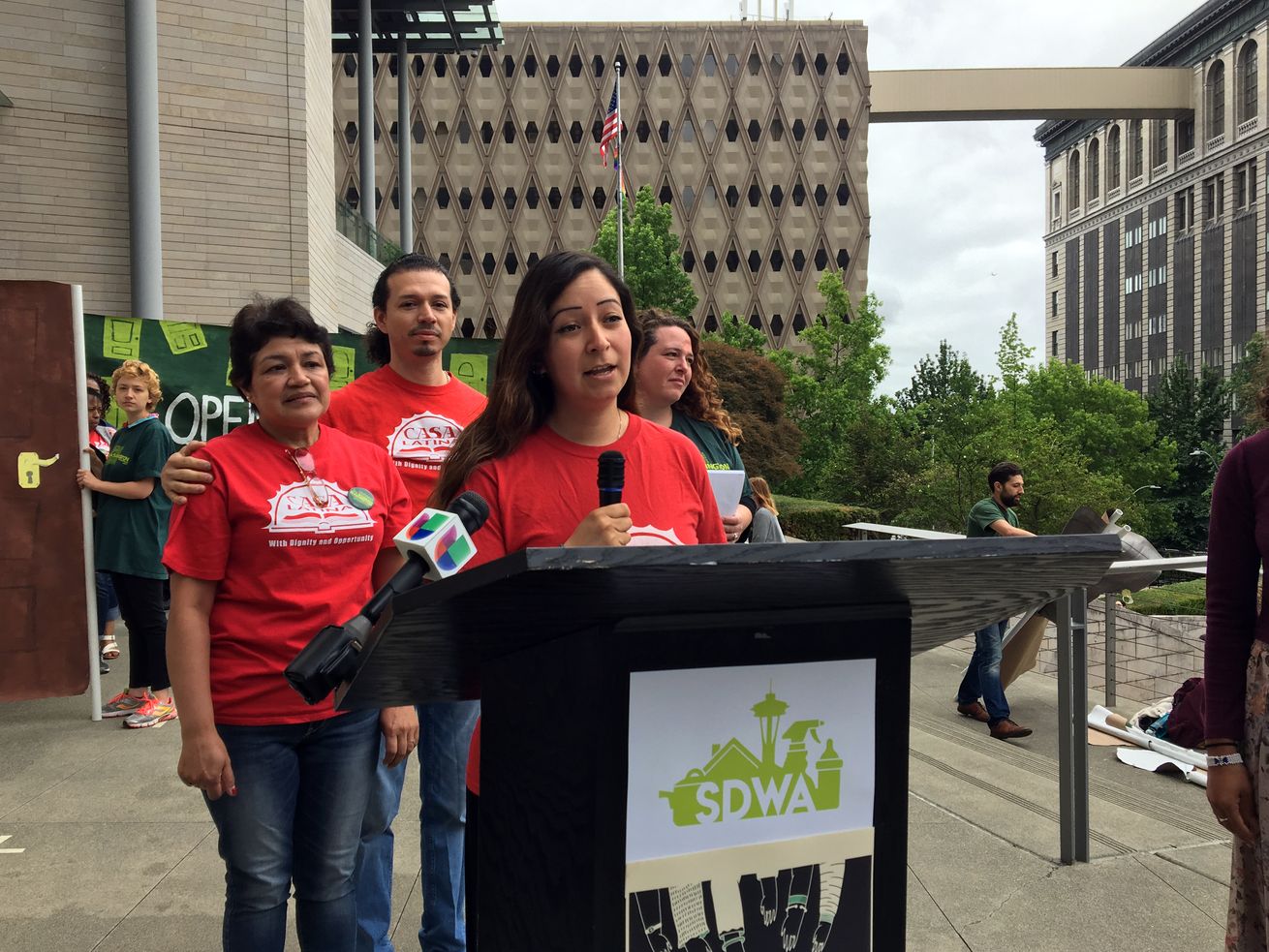

As a housecleaner, Burgos belongs among the 30,000 workers in Seattle who call themselves domestic workers, a group that also includes nannies, gardeners, cooks and household managers. Occupying the so-called “gray labor market,” these workers face substandard wages and conditions with few connections to recourse if they are mistreated.

Federal labor laws don’t afford many domestic workers the same standards and protections as workers in more visible industries. Legislation introduced by Seattle City Councilor Teresa Mosqueda this week aims to change that.

Mosqueda’s legislation, known as the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, would prohibit employers from paying domestic workers less than minimum wage and guarantee breaks. It would also make it illegal for families to keep the personal documents of domestic workers, such as passports or work permits.

Finally, the legislation would create a domestic workers standards board, the first of its kind in the nation. The board would be tasked with making recommendations to the city on training requirements, accreditation, wage standards, benefits and hiring agreements. Domestic workers would fill four of nine positions on the panel.

“A group of workers excluded from federal labor standards due to racism & sexism will be leading the way to a new model of worker power,” said Sage Wilson, spokesperson for the labor advocacy group Working Washington. “It’s a total breakthrough in the United States.”

During a press briefing Thursday, Mosqueda stressed that women, immigrants and people of color dominate the field.

“Today is about justice. Today is about dignity,” Mosqueda, a longtime labor organizer, said.

Seattle’s proposal follows similar legislation in New York, California, Oregon, and other jurisdictions.

More than half of the 30,000 or so domestic workers in Seattle live below the federal poverty line, according to a report sponsored by a coalition of labor groups called the Seattle Domestic Workers Alliance. Researchers also found that most domestic workers in the city don’t receive overtime pay, health insurance, or paid family leave.

Adelaida Elington, a housecleaner from Guetamala, told council members that she is taking pain medication as a result of not having enough time to rest and recover. “Being a housecleaner is a physically demanding job. We have to use our whole body while doing this work,” she said during a committee meeting. “That’s why I’m coming here to open the door and tell you that’s not fair.”

The bill stands a good chance of passing. Seattle’s City Council in recent years approved numerous labor standards, including rights for drivers for ride-hailing apps to unionize (although that one’s tied up in court), requirements for bosses to give employees predictable work schedules, and the $15 minimum wage.

Mayor Jenny Durkan supports the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, and no organized opposition has emerged since council members said they would to craft a bill last December.

Mosqueda introduced the bill during a Thursday meeting of the Housing, Health, Energy and Workers’ Rights Committee. She said she expects the committee to work on the bill for the next four to six weeks before sending it to the full council for a vote.

This article has been updated to clarify Sage Wilson’s role at Working Washington.