Ask any dieter: the last ten pounds are the hardest.

For the past several years, Seattle has been racking up amazing year-over-year declines in the percentage of downtown commuters who arrive by single-occupancy vehicle, despite adding tens of thousands of new jobs and residents. This didn’t happen magically – it required hard work and coordination from various agencies and employers (and voters) to create viable alternatives to driving.

But even though a 25% drive-alone rate is pretty darn low, and the envy of our peer cities in America, it’s not low enough. Downtown will be a mess for the next few years, and we need to take even more cars off the road to have a chance of keeping things moving.

The last few percent are the hardest.

Think about public transit as a product. Product marketers often look at customer acquisition costs (CAC). For a startup, CAC is low: early adopters will seek out your product on their own. As your product saturates the early market, you ramp up advertising and expand the product line to serve more marginal customers, who don’t see the immediate value of the initial product. In the transit case, this means an increasingly expensive (in political capital if not dollars) battery of carrots and sticks is deployed to entice the remaining holdouts out of their cars.

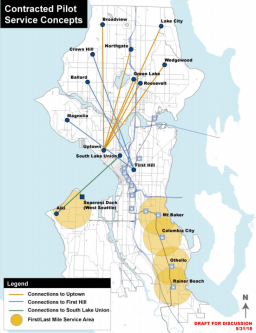

Which is how we end up with a SDOT proposal to add private shuttles to the mix of transportation options. The agency looked at the data and identified several trip pairs to downtown-adjacent neighborhoods like First Hill and SLU that typically require 2-seat bus rides where the drive-alone rate is the highest, and proposed a pilot program to provide one-seat, peak-only rides between these areas. The pilot would have run for a few years until the TBD levy ran out, coinciding with the worst of the One Center City congestion.

Ideally SDOT would have continued to contract with Metro for these additional services, but Metro’s base capacity is maxed out in the afternoon peak. So the city tried to get creative and proposed hiring a private contractor.

From a technical perspective, one wonders how many new riders the shuttles would have gotten, versus cannibalizing existing riders (SDOT was projecting 3,000 daily riders in year two). Or how much it would have cost per rider to have empty shuttles deadheading back to the neighborhoods (though it might have been worth it… a high CAC is to be expected).

Opponents latched on to the privatization angle as a camel’s nose under the tent for further privatization of public services. The fear is understandable, especially in the Trump era where public resources are auctioned off willy-nilly, but Metro already contracts with private companies to deliver dial-a-ride (Access) service. While Access certainly has issues, it hasn’t led to any kind of slippery-slope wholesale privatization of bus service in the county (Transdev and Solid Ground provide existing Access service and would have presumably been candidates for the SDOT shuttle program). The RFP process would have been a fine time to hammer out any concerns about safety, training, or wages.

Anyway, given the recent head tax contretemps, killing the pilot was an easy vote for a beleaguered Council. (It didn’t help that privately-run microtransit has had a bad run lately.) Still, the period of maximum constraint is real, and we need an all-hands-on-deck approach in the next few years that gives priority to non-SOV modes. That includes:

- All-day transit priority on 3rd avenue

- Better service to First Hill and SLU, such as extending Route 40 up Yesler

- Real enforcement of existing bus lanes

- More bus lanes, not just in downtown but on the approach roads

- Congestion pricing

- Better transfers at Montlake/Husky Stadium

- The basic bike network

In other words, the first priority ought to be moving the existing buses faster before we start adding more transit vehicles of any kind. How many more marginal riders would switch to the bus if it were actually faster? How much more frequently could the existing buses run, with the existing base capacity, if they weren’t stuck in traffic? These are the question we ought to be asking as cars continue to dominate downtown right-of-way. Then let’s talk shuttles.

The One Center City near-term action strategies cover some of the above points. The TBD looks like it will be modified to allow up to $20M/year to be spent on bus capital improvements and RapidRide, which should help with speed and reliability. But more can be done. And translating it all into increased bus ridership for that marginal rider will require a healthy dose of political leadership.

![]()

![]()